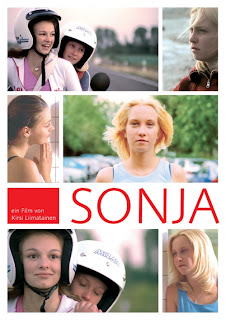

Director: Kirsi M. Liimatainen.

Principal cast: Sabrina Kruschwitz, Julia Kaufmann, Nadja Engel, Christian Kirste.

Growing up is never easy, especially if you feel alienated from most of your peers. For some people friendships from their childhood and/or adolescence will continue unhindered also in their adult lives while for others it may never work out that way. Puberty brings about a few changes – in one’s perception of what’s cool and what’s not, what matters and what doesn’t, but especially it changes one’s perception of the surrounding people. Slowly but steadily they become sexual beings and one’s own sexual awakening inevitably leads to a reassessment of one’s hitherto so relatively uncomplicated friendships. „Alpha” males start having fights over girls and cheerleader types have their own quarrels over guys. This is perceived by most societies as the „normal” adolescent behaviour and it is also expected that you start to take an active interest in the opposite sex when you reach a certain age. But what do you do when you fall in love with someone of your own sex on top of having your general teenage confusion about everything else? What do you do when the person you are madly in love with has been your best friend since the early grades in school? Kirsi Liimatainen’s first long feature film „Sonja” tries to deal with the complexity of not just leaving the childhood world behind and entering adult life but also a teenager’s growing realisation of not having the „mainstream” sexuality in a world full of patterns to be followed and expectations to live up to.

Sonja, our 16 year-old protagonist, lives with her divorced mother in one of those parts of Berlin which many Germans call „Trabantenstädte” – endless grey blocks of flats built by the former government of „workers and peasants”. The blocks look dreary and so do the people living in them. Ordinary grey people in ordinary grey blocks with ordinary grey (more in mood than in colour, though) GDR-era wallpaper. The local lads seem to be preoccupied with cars and dating girls while the local girls mostly seem to be reading magazines about finding a boyfriend and evaluating the options at hand. Sonja is no exception as such. She hangs out with the other girls and even has an „official” boyfriend, Anton. Nor is there anything strange or rebellious about her clothes or hairstyle. Just an ordinary girl who doesn’t stand out in any particular way. But there is something wrong. She doesn’t understand what it is and why, but nothing feels right. She much prefers the company of her best friend Julia and finds her having to spend time with Anton suffocating. She isn’t very interested in the magazines’ tips. And she doesn’t find it all that exciting to sneak into guys’ rooms after curfew at a local sports camp. She constantly quarrels with her mother and hardly ever replies when other people approach her (which isn’t that uncharacteristic for a moody teenager, of course) but then she blossoms up when she is in Julia’s company. All of Sonja’s body language indicates that she is drawn to her and that she sees in Julia a lot more than one would in just a friend. Girls being traditionally allowed a greater intimacy with each other in Western culture won’t encounter many scornful looks or ugly remarks walking hand in hand publicly or having slumber parties. One can say that Sonja takes advantage of that in a way because Julia doesn’t find it strange that her best female friend sleeps in the same bed as she at the sports camp while drawing imaginary circles on her naked back, calls her the most beautiful girl in the world in the shower and is generally very straightforward and consequent in her flirting with Julia. One night she even reads love poetry to her. And although Julia is fairly responsive to Sonja’s attention, there is always this invisible line which Sonja doesn’t dare to cross. At the same time, Julia constantly flirts with guys and even occasionally snogs them in front of Sonja who, unsurprisingly, feels very jealous but is unable to do anything about that. This, naturally, only adds to her frustration and confusion.

At one point, Sonja is sent to the Baltic Sea coast to visit her father. She is supposed to go there together with Julia, but plans suddenly change. Julia has just lost her virginity and has no interest in deserting her new-found boyfriend. Sonja will have to face her father’s family alone. Before leaving, she had split up with Anton. All they had ever tried was kissing and now that Julia has taken the step from being a girl to becoming a woman (at least, in the traditional sense), she feels that she has been left behind in more than one way. She is also very confused about her feelings for Julia and how „appropriate” they are. Maybe her emotions will change if she gives herself to a man? She makes an awkward attempt at „awakening” heterosexuality inside her by letting herself be seduced by a neighbour. Inevitably, this experience only confirms what she hasn’t dared to acknowledge until now – that she is in love with Julia and that she is lesbian.

„Sonja” is based on Kirsi Liimatainen’s own experiences growing up in her native Finland and her first love, unreciprocated like Sonja’s. She also grew up surrounded by dreary housing and fairly ordinary people, where „a man is a man and a woman is a woman” as Sonja’s father postulates at one point at the dinner table. It can be very difficult (if not to say, rather dangerous for one’s health) to come out as a gay man or a lesbian woman in such an environment, but the fact is that one can more often than not leave this environment and seek a broader-minded community elsewhere. One’s coming-out process towards the outside world is very important, but what’s even more important is being able to come out to oneself. The road that leads to the understanding and subsequently acceptance of one’s own sexuality is not a motorway, it’s rather like a narrow path in a thick forest where you have to fight your way through the unhospitable bushes and intimidating branches hanging low from the cold and unforgiving trees. And the unfortunate truth is that for the most part you have to walk that path on your own. Sonja’s feelings of not fitting in and being alone with her confusion are far from being unique in any way. They say that road to hell is built on best intentions – the intentions of one's parents, friends and the society one lives in. And their intentions are usually "to straighten you out" which will only make your path through that forest even harder to walk. Alas, this still applies to most parents, „friends” and societies on this planet. At least, that seems to be the case.

„Sonja” is a warm film about a cold world. It is also a rather slow and thoughtful film. A great part of the dialogue is in fact body language which shouldn’t really surprise anyone since the director is Finnish and the settings are German. The acting is very convincing and realistic, although I believe that for the most part it comes from the fact that the actors don’t really have „to act”. Portraying an „ordinary” German girl shouldn’t be very difficult for somebody who herself can be described as an „ordinary” German girl. And the same goes for the other characters in the film. In fact, they seem so ordinary that it feels like you’ve met them yourself sometime just passing through those dreary blocks of flats in East Berlin or anywhere else in Europe. In this respect, it reminds me of another German film, „Nachbarinnen” („Neighbours”). The beauty of them both lies not in grand settings or a riveting drama, but the simplicity of the complicated. Enough said.

Here you can watch the film's trailer from Picture This!